If you’ve been in Python-land for long, you’ve probably seen some @-sign thingies hovering (often mysteriously) above functions and class definitions, saying things like @patch or @classmethod or perhaps something even more obscure. Maybe you already know that these are called “decorators”. Maybe you’ve even used them, or written your own!

Even if you’ve done all that and still don’t quiiiite get what’s going on under the hood with decorators… don’t worry, my friend, you are not alone. Heck, I’m still not quite sure what goes on under the hood with decorators, but after a very productive afternoon of fiddling, I have a much better idea, and I’m here to share the fruits of that fiddling with you. Ready? Here we go:

Decorators are callables called on callables that return a callable which then replaces the original callable.

Got it?

…No?

…Yeah, okay, that’s fair. Let me try that again.

A Temporary Oversimplification

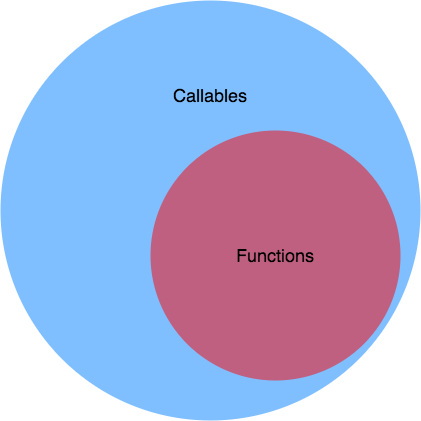

I know I said “callable” up there before, but just for now, I’m going to simplify and instead of talking about “callables”, I’ll talk about “functions”. All functions are callables—i.e. “functions” are a subset of “callables”—and they tend to be the easiest case for people to wrap their heads around.

“Callables” can also be classes, or heck, most any object, if it’s got the appropriate set of behaviors. We’ll dig into that in a bit, but for now, let’s talk about decorators in terms of “functions”. With this simplification in mind, let me amend my definition above to make it maaarginally less confusing:

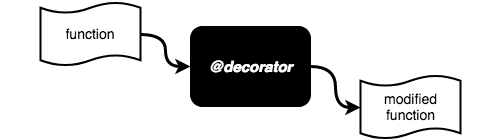

A decorator is a function (dec(…)) called on a function (fn(…)) returning a function (fn_decorated(…)) which then replaces the original function:

@dec

def fn(...):

...

# Is approximately equal to:

fn = dec(fn)

How Decorators are Applied

Say we’ve got this function. It doesn’t do much, but it’s a nice little function:

def times_two(x):

return 2*x

But say that we’re so excited about that function that we want everyone to know when we call it, so we’re gonna sound a klaxon every time we do:

def times_two_with_alarm(x):

print("WOOP! WOOP! WOOP!")

return times_two(x)

Sure, that works. But what if we’ve got a BUNCH of functions that we’re really excited about, and we want to add this big ‘ol alarm (by which I mean “print statement”) to all of them? It’ll get repetitive to add that code everywhere; what if we just wrote a function to stick that print statement into our functions for us?

def add_alarm(fn):

def fn_with_alarm(*args, **kwargs):

print("WOOP! WOOP! WOOP!")

return fn(*args, **kwargs)

return fn_with_alarm

add_alarm is a function that takes an argument fn, the function we want to add an alarm to: it then returns us a NEW function which does the following:

a) sound the alarm

b) invoke the original function we passed to it

In practice, then, we can achieve the same thing we achieved above like so:

times_two_with_alarm = add_alarm(times_two)

Because, remember, in Python, functions are first class objects; they can be passed around, passed as arguments, assigned, etc. In this case, add_alarm takes a function as an argument, and it returns a function (one that does whatever the original func. does, but this time with an alarm). We can then assign the output of add_alarm; so now, times_two_with_alarm is that new, modified function:

> times_two_with_alarm(5)

WOOP! WOOP! WOOP!

< 10

Heck, maybe we don’t want to keep track of a whole different function name, we just want that alarm to be baked into our times_two function. Well, we can do that too:

# In case you forgot, here's how we defined this function...

def times_two(x):

return 2*x

# Add the alarm to it!

times_two = add_alarm(times_two)

> times_two(4)

WOOP! WOOP! WOOP!

< 8

Okay, But Like… You Haven’t Used a Decorator Yet…?

Geez, I’m getting there! In fact, THIS is where decorators come in! If the above seems a little tiresome, we can use this shortcut:

@add_alarm

def times_two(x):

return 2*x

The @decorator syntax means basically what we said above: “define this function, but then run it through this other decorator function, and assign the result of that call (which, again, ought to be a function) back to the function I just defined.” This way, you can easily modify multiple functions in predictable1 ways, and moreover, modify them in place; no need to keep track of both times_two and times_two_with_alarm, just update times_two to do the new thing.

Back to “Callables”

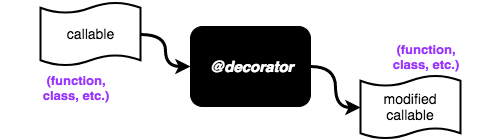

So remember earlier when I waved a hand and said that we’d talk about decorators as “functions that manipulate functions”? Well it’s actually a bit gnarlier than that. Properly speaking, decorators are callables that manipulate callables, and as such, both decorators and the things they decorate may be functions, or they may be random other stuff.

What’s a “Callable”?

A callable is anything that you can call—i.e. anything that you can stick a () after (with maybe some arguments inside) and have something happen. A callable may be a function (my_func(...)) or a class (MyClass(...)2), or (as helpful as this definition is) any object, as long as it can be… well, called. Some things that are NOT callable include strings, ints, lists, etc.:

> "hello"()

< TypeError: 'str' object is not callable

So then, to re-visit our original definition of a decorator, taking away our initial oversimplification: decorators are callables that manipulate callables (and then replace the original thing with the modified thing).

We’ve already talked about decorators as functions being used to modify functions. But since callables can be either functions or classes (…or objects, but we’ll ignore that for now), let’s talk about some other cases.

Decorating a Class with a Function

What if we just got really excited about a bunch of classes, and wanted to announce to the world whenever we made a new instance of one? It might look something like this:

def announce_new_instance(cls):

def make_new_instance_with_announcement(*args, **kwargs):

print("Making a thing!")

return cls(*args, **kwargs)

return make_new_instance_with_announcement

@announce_new_instance

class MyClass():

def __init__(self, foo):

self.foo = foo

> MyClass('bar')

Making a thing!

< <__main__.MyClass at 0x10fd84b70>

Recall that MyClass is a callable—MyClass() means, “make me a new MyClass instance!”—and so we can treat it just like any other thing that can be called, and even treat it like the function from our first example. In this case, under the hood, we’re replacing MyClass (the function-like thing that, when called, makes a new instance) with make_new_instance_with_announcement, which makes its announcement and then kicks off making a new instance. (In the context of the decorator above, cls represents the class you passed in, i.e. the class you’re decorating; so here, it’s MyClass, thus cls() is the same as MyClass().3

Classes as Decorators

This one bends my brain, but you can totally use a class as a decorator! Because as we discusssed (say it with me), classes are callables too. A call to MyClass(*args, **kwargs) eventually calls out to MyClass.__init__(self, *args, **kwargs) (and does some other magic such that at the end of it all, an instance is returned back). There are probably other rad things you can do with classes-as-decorators, but the pattern I’ve seen most often (in all three hours of looking into this) is this one:

class DecoratorClass():

def __init__(self, fn):

self.fn = fn

def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs):

print("Look how decorated!")

return self.fn(*args, **kwargs)

@DecoratorClass

def times_two(x):

return 2*x

> times_two(41)

Look how decorated!

< 82

Oh man, weird, right? DecoratorClass is a class that takes a function (fn) as an initialization argument and hangs onto it. And recall that we replace the function-to-be-decorated with the result of a call to decorator, thus the above is equivalent to:

def times_two(x):

return 2*x

times_two = DecoratorClass(times_two)

That is, the new times_two is an instance of DecoratorClass?! What?!

> times_two

< <__main__.DecoratorClass at 0x109b867b8>

But the point of decorators is that we don’t really care what times_two is, we just want it to do what we expect when we call it. Thus, we need an instance of DecoratorClass to actually DO stuff when you stick (…) at the end. That’s where the __call__ method we defined earlier comes in.

Tangent: __call__

We can make an object (i.e. an instance of a class) callable using the magic __call__ method, like so:

class Callable():

# defining the __call__ method on an INSTANCE of this class

def __call__(self):

return "you called me!"

> c = Callable()

> c()

< "you called me!"

# Contrast with...

class NotCallable():

pass

> nc = NotCallable()

> nc()

< TypeError: 'NotCallable' object is not callable

Back to DecoratorClass

So we’ve got a DecoratorClass that takes in a function and hangs onto it, and when we define the magic method __call__, we’re defining what happens when we stick (...) on the end of an instance of this class—we call the function that we passed in in the first place:

> instance = DecoratorClass(times_two)

> instance(5) # i.e. DecoratorClass.__call__(5)

Look how decorated!

< 10

So after all that decorator magic, we’ve replaced times_two with an instance of DecoratorClass, right? But as we just saw above, we can call that instance like we would call any other function; thus times_two can still be called like normal, and in all respects treated as a normal function—but now it has some shiny extra functionality added via our decorator.

Okay, But Why Would You WANT to Use a Class as a Decorator?

That’s a great question. There are probably lots of fascinating answers. At this present moment, I only have two: “to store state” and “because you can”. Since I’ve already covered the latter in quite a bit of detail, let’s turn to the former, i.e., a halfway plausible case in which you might want to use a class as a decorator. (I’m sure there are other reasonable ways to store state on a function, as well as other compelling reasons to use classes as decorators, but let’s just go with this for now.)

Unlike functions, which are (generally) one-and-done, classes allow you to store state.4 How might you use this in a decorator context? Consider something like this:

class countcalls():

def __init__(self, fn):

self.fn = fn

self.CALLS = 0

def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs):

self.CALLS += 1

print("This func. has been called {} time(s)".

format(self.CALLS))

return self.fn(*args, **kwargs)

@countcalls

def foo():

return "hello world"

> foo()

This func. has been called 1 time(s)

< "hello world"

> foo()

This func. has been called 2 time(s)

< "hello world"

And heck, why not go for broke and use a class to decorate a class?!

class countinits():

def __init__(self, cls):

self.cls = cls

self.INITS = 0

def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs):

self.INITS += 1

print("You've made {} of this class".format(self.INITS))

return self.cls(*args, **kwargs)

@countinits

class MyClass():

pass

> inst1 = MyClass()

You've made 1 of this class

> inst2 = MyClass()

You've made 2 of this class

The above example looks a little gnarly, but remember that cls here is MyClass which is a callable (that makes and returns a new MyClass instance), and remember how the @decorator syntax is applied, and you can piece together precisely what dark magic is happening here.

Awesome! …Wait, What?

Yeah, I know, a lot of things just went down. To summarize:

- you can decorate any callable—be it a function, a class, or any callable object.

- a decorator—the

@somethingthing—is a callable (function, class, etc.) that takes as an argument the thing you’re decorating and returns another callable that preserves the original functionality but adding something new - the type of callable is irrelevant. Functions can decorate functions, or classes, or objects. Classes can decorate functions, or classes, or objects. Basically, anything goes.

There are lots of other resources on the interwebs about what sort of stuff you might want to use decorators for—and heck, I might write a blogpost about some of them in future—but I hope this is an illuminating overview of just what the heck decorators are and how they work. As always, feel free to reach out with any questions! A big thank you to all the excellent folks who beta-read/edited this post: Ben Anderman, Codanda Appachu, Sam Auciello, and Alex Burka.

-

…except that decorators as described here can potentially do weird things to doc strings and other function attributes. This is one of the reasons that many folks use

functools.wrapswhen decorating things: it copies over most (though not all 😞) of the original functions’ hidden attributes to the new, wrapped function. Hat tip to Codanda Appachu for reminding me of this. ↩ -

MyClass(...), of course, being shorthand forMyClass.__init__(...). (That’s totally an oversimplification;MyClass(...)is actually shorthand forMyClass.__new__(cls), which does a bunch of stuff, including call__init__on the newly madeMyClassinstance… but sufice it to say that when I callMyClass(...)I expect some stuff to happen, including a call toMyClass.__init__, and to eventually get back a new instance of that class.) ↩ -

Note that since

MyClass(...)is baaasically shorthand forMyClass.__init__(...)(see above), and so you can achieve a pretty similar effect by decorating the__init__method. The thing passed intoannounce_new_instanceto be transformed will be different, but the new function will execute in just about the same way. ↩ -

Hat tip to Jayant Jain, who pointed out an error I made in the original version of this blogpost. (Yes, if you really wanted to, you could store state on a function as well, cuz it’s Python and everything is an object, including functions. For instance, I could totally set

my_func.some_value = "hello". However, it’s awkward and unidiomatic. So like, go ahead and do that if you want, but it’s kinda weird, and really it just makes more sense to use classes.) ↩