Back in mid-July, I started at Hacker School, wide-eyed and green and totally freaked out. With only a little bit of Javascript under my belt (and a basically negligible amount of Java, so we’re not even counting that), I decided to teach myself Python, slogged halfway through Zed Shaw’s Learn Python the Hard Way, then went off to go build something, because I work best by getting my hands dirty. For my first Python project, I wrote studentchooser, a little command-line app requested by a teacher friend of mine, who wanted a fair way to call on her students at random (for putting homework problems on the board, etc.). The idea was that, once a student had been selected, it was less likely that they would be selected again, but not impossible—the chance of them being picked subsequently would go down, but they would still be in the running.

So, I made a program to do that! You store a list of students for a given class period in what I called the roster (just a dictionary of students). Each Student object keeps track of the number of times it has been selected and its probability of being selected in the next round, as well as whether or not the student is absent.1 It took me a little more than a week to finish, as I was still muddling through Python as I went, and at the end, I had a working final product! A rough one, but a working one! And then I went off on my merry way, doing more and varied projects and slowly building up my Python chops, getting code review, etc. Somewhere along the way, so gradually I didn’t even realize it, I began to feel competent, like with enough time to think and maybe a little Googling, I could Python my way out of most problems that were thrown at me. And so today, back at Hacker School for Alumni Thursday and itching to write some code (because I’ve been up to my neck in web work for the past few weeks), I opted for a blast from the past, and dived into my very first Python project to poke around, refactor, clean up, and chronicle what I found and what I had learned in the past four months. Here are some findings, accomplishments, and reflections.

Little things I changed

There were a handful of little things that now strike me as really silly that I changed straight off. Stuff like the realization that text files don’t actually need an extension (.txt or otherwise), or that instead of myfile = open("foo.txt", "r"); contents = myfile.read(); myfile.close() I could do the whole thing more cleanly and more efficiently with with open("foo.txt") as myfile:. Similarly, I found loads of places where a little more specificity in variable naming would have made the code hugely easier to read. So given something like, say, for item in roster_list, I changed it to for roster_name in roster_list.

Gratuitous, “useless” comments

There were comments EVERYWHERE. Like seriously, look at the code sample below.

"""Load a roster from file."""

# Boolean saying that this is NOT a new roster

# i.e. when the program saves data, it will NOT edit the "config" file

global new_roster

new_roster = False

# make list of all rosters in config file

roster_list = get_all_rosters()

if len(roster_list) == 0: # if list is empty, make a new roster instead

print "No rosters available to load. Make a new one instead."

make_new_roster()

else: # if config file contains at least one roster to load...

print "Which roster would you like to load? Enter a number."

# print a list of available rosters from config file

for item in roster_list:

item_index = roster_list.index(item) + 1

pretty_name = get_pretty_name(item) # (name of the file w/o the file extension)

print "\t%d. %s" % (item_index, pretty_name)

while True:

answer = ask()

# if possible, turn answer from a string into an int.

try:

answer_int = int(answer)

except ValueError:

answer_int = None

# if the answer is an int. in the range of # items in the list...

if answer_int in range(1, len(roster_list) + 1):

index = answer_int - 1 # (b/c list as displayed is 1-indexed)

# save the given filename as the 'current file'

global current_file

current_file = roster_list[index]

print "File to load:", current_file

# populate the roster using the data in the selected file

populate_roster(current_file)

# returns name of the class (= name of the file) for display

return get_pretty_name(current_file)

else: # if user input isn't in range or isn't an integer

print "Sorry, I didn't get that. Try again." # run the loop again

This comments-every-step-of-the-way thing pops up again and again in studentchooser, and looking at the code now, it seems pretty silly, because I can tell just by looking what most of these lines do—or at least, I can after rewriting it a bit so that variable names are intuitive, code is readable, etc. So I took a lot of these comments out of the refactored version, but I think it’s really important to remember why I put them in in the first place. When I was first writing this code, it wasn’t gratuitous, it was super helpful to know step by step exactly what was happening in my code, and to write it down so I couldn’t get away with fudging that understanding. This is actually one of the few things I really took with me from Learn Python the Hard Way (see for instance these study drills—that explaining your code in English line by line is a great tool for understanding and internalizing it! This is something I still keep in my toolbox for unknown/particularly tricky bits of code.

Now I know better…

This project has a) no tests, which make it a giant pain to refactor; b) haphazard architecture, because I was adding features as they occurred to me and I didn’t go in with an overarching plan, and so variable names are unclear, patterns of work are inconsistent, bits of the code are held together with tape and bubble gum, etc., and c) poor readability, due in part to the inconsistent naming schemes, in part to the fact that I wasn’t prioritizing readability and didn’t know how to code for it, and in part to the fact that I thought gratuitous commenting would make up for hard-to-read code. Now I know better, or at least I hope I do. (When I’m not lazy,) I write tests for my projects; I outline my projects ahead of time and plan for the features I may add in the future so the architecture stays coherent and I don’t have to refactor halfway through (hopefully); and I strive for readability in my code itself (and don’t rely on gratuitous commenting to do that work for me).

New tools, new sensibilities

I first learned about list comprehensions when Tom code-reviewed this project for me, though I didn’t really understand what they were until much later—I initially thought they were something cool you could do in a return statement, which now makes me laugh. But now that I actually understand list comprehensions and a bunch of other handy tricks, I can write much tighter, more efficient code. What used to be this:

def get_all_rosters():

""""Return a list of all of the roster filenames in the config file."""

all_rosters_file = open(config_file)

all_rosters_list = []

for line in all_rosters_file:

all_rosters_list.append(line.strip())

all_rosters_list.sort(key=string.lower)

all_rosters_file.close()

return all_rosters_list

…is now this:

def get_all_rosters():

""""Return a list of all of the roster filenames in the config file."""

with open(config_file) as all_rosters_file:

return sorted([line.strip() for line in all_rosters_file], key=string.lower)

This code is more compact not only because of the list comprehension (did I mention that list comprehensions are awesome?) but also because I smooshed the sorting into the same line as the list-making. There are other cases where before, I make a list, joined it into a string, and returned the string, but now, I return-a-join-this-list-into-a-string-please-thx-bai, all in one line. The more comfortable I get with Python, the less I need to separate things out and the more able I am to smush things together into fewer lines while still knowing what’s going on.

Global variables, global variables everywhere!

By far the biggest pain in the neck about this whole program was keeping track of the global variables. I had a few of them floating around: a roster where I stored all of my students, a list of the students (because for some reason I needed to keep a separate list instead of just extracting it from the roster), the filename under which this roster was stored, a boolean telling me whether this was a new roster or not… And so every time there was a function that needed to interact with and modify, say, the roster, it had to go look for this global variable called roster (I guess because I didn’t think to pass in the roster as an argument).

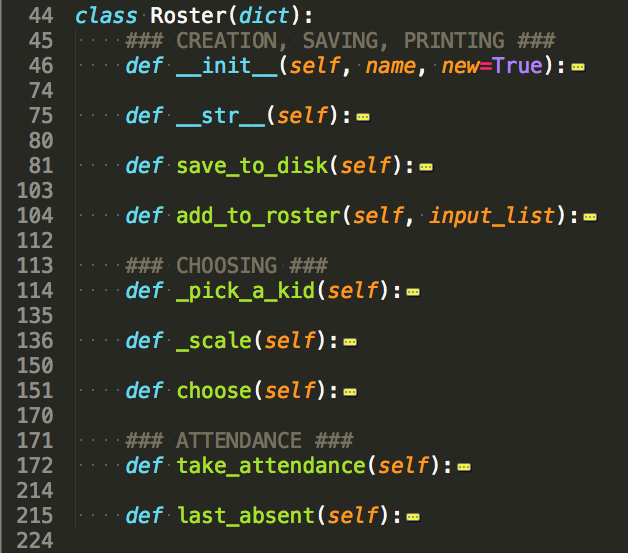

The solution to my dilemna? Classes!

I made a Roster class so that methods like choose(), instead of finding the global variable roster, accessing it, changing it, and sending it back into the ether to live its global-variable life, would instead be called as myroster.choose() and act on that specific instance of Roster, and there would be no confusion as to what the method was accessing/modifying. This refactoring solved another handful of problems, because I could decree that file names would be the same as roster names, and so myroster.name would also keep track of our current file name; similarly, myroster.new2 would keep track of whether or not this was a newly created roster. Basically, the Roster class let me get rid of all of my global variables, and now all I have to keep track of is the current_roster object. (Also, now I know better than to make it a global variable; if there are functions that need to access it—which I have tried to minimize—I pass it to that function as an argument.) Check out a high-level view of my Roster class to see all the functions contained therein:

In conclusion

I refactored some code and had a total blast from the past. I decided to see what I could improve without changing any of the functionality, just the code, and I cut my program from 536 lines down to 432, and to 399 if we remove vestigial testing functions. That’s about a 20% reduction in length! I also convinced myself that I do, in fact, know how to write Python, and checked in with myself about how far I’ve come in the last four months. I obviously have loads more to learn—and this exercise reminded me of some of the helpful strategies in my toolbox, like temporarily over-commenting to wrap my head around whacky and confusing code.

So, after reflection, my advice to new programmers who are jumping in the deep end like I did? Get your hands dirty. Write lots of code, without necessarily caring about what the finished product looks like—you’ll learn so much more from finishing it and fixing it later than you will from agonizing over it. Get code review and pair with people who know more than you do—it’s how you pick up the stuff that makes you a better programmer. But mostly, don’t panic!

(This is a blog-ified version of a Hacker School Thursday Talk presentation given on 11/20/14.)