I’ve been working with SPARQL a bunch for my OPW project, and found it very slow going at first. SPARQL is apparently one of those little-loved languages that doesn’t have much in the way of tutorials or lay-speak-explanations online—pretty much all I could find were the language’s official docs, where were super technical and near-impossible for a beginner to slog through. Hell, I didn’t even understand what the language did—how could I read the technical specs?

So, I decided to take a step towards remedying this problem. This post won’t actually teach you how to use SPARQL—others do that better than I, and I provide some links at the bottom of the post—but it’s intended to be a primer on how SPARQL works, and what the data you might use it on looks like. (This is a blog-ified version of a Hacker School Thursday Talk presentation given on 2/5/15.)

What is SPARQL?

It’s like SQL, but with extra unicorns.

No really, what is SPARQL?

Besides a query language with a really ridiculous name?

SPARQL is a (recursive) acronym standing for: SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language.

It’s a query language, like SQL, that you use to poke around in your data and find the bits of it that you want. Unlike SQL, which queries tables, SPARQL queries data stored in a different way: a Resource Description Framework (or RDF).

What is RDF?

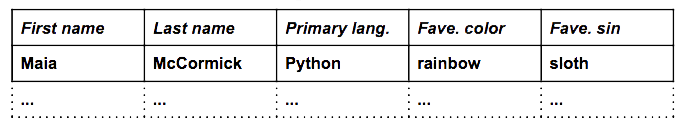

SQL expects data to be in tables, like this:

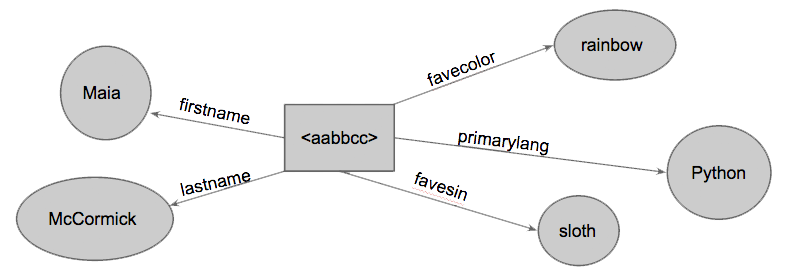

But SPARQL works with data organized like this:

A single row in the SQL table is a collection of bits of information about that one entity (in this case, a person); the web below is another way of visualizing that information. Each bit of information is contained in a subject/predicate/object triple.

Subject/Predicate/Object Triples

SUBJECT – PREDICATE – OBJECT

This convention plays off of English grammar constructs [fn: and probably lots of other languages too, but I don’t know enough linguistics to make any sort of comprehensive claim] grammar constructs. In English, we can make a sentence like this:

The human – throws – the ball.

The human is the subject, throws is the predicate (verb-like thing), and the ball is the object. Likewise, we can express any cell from a SQL table in the same way:

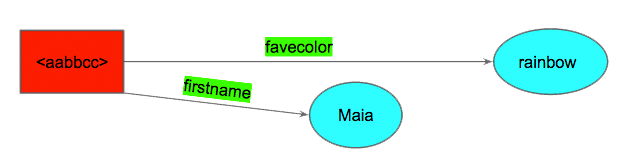

Maia – has favorite color equal to – rainbow.

Where Maia (the thing we’re referring to—the row in the SQL table representing an entity) is the subject, has favorite color equal to is the predicate (think of this as the property name, or put another way, the column header), and rainbow is the object (the value of that property for the given entity). In diagram form, it would sort of look like this:

Only, this is not quite accurate. Maia is not its own entity; it’s a human-readable identifier (what we mortals call a first name) for some entity stored in your computer. This entity hasFirstName Maia just like it hasFavoriteColor Rainbow. So in reality, the visual representation would look more like this:

<aabbcc>—the alphanumeric string we give to our entity to represent it and so we can track all of its associated properties and value—is called a Uniform Resource Identifier, or URI. (Not to be confused with Uniform Resource Locators, or URLs. A URL tells you the location of the entity in question, where as the URI is the name the computer has given to our entity; think of a URI as a name and a URL as an address.)

What Does a Query Look Like, Anyway?

The first thing to know is that SPARQL objects and properties aren’t invented at random. When you’re using SPARQL, you work with a predefined set of classes (e.g. contact, email address, etc.) and properties (e.g. hasFirstName, dateAdded, etc.), collectively called an ontology. Generally, systems will use a combination of the standard ontologies floating around the web (GNOME Tracker, for instance uses this collection of ontologies, someone putting together a contacts list might use foaf). I also assume you can make your own, though I’ve never experimented with this. Ontologies are identified by a prefix (and if you’re writing your own queries from scratch, you’ll have to set the prefixes with a link to the ontology on the interwebs)… The point being, in English, you might get confused between “has first name” and “has name” and “is named” and “has given name”… but in SPARQL, there will be only one name for that property (presumably something like foaf:givenName).

Anyway, what does a query look like? It looks something like this:

SELECT ?a ?b ?c

WHERE {

...

}

ORDER BY ?a

LIMIT X

Basically, you select some stuff (SELECT ?a ?b ?c as specified by the conditions in your WHERE clause—possibly including some FILTER statements) which you can then do a handful of operations on: ordering by one or more of the values, capping the number of results you want, etc.

But that was (obviously) an extremely sketchy description, and as I warned you, I’m not going to go into any more detail in this post. Others have tackled this material better than I—I learned most of what I knew about SPARQL at the very beginning from Dr. Noureddin Sadawi’s Simple SPARQL Tutorial, in which he plays around with Bob DuCharme’s sample code. Check out their stuff to learn what queries actually look like, and all the cool stuff you can do with them. I hope this has been at least somewhat enlightening; thanks for tuning in!